Public Valuations Are Setting The New Climate Startup Valuation Benchmarks

Over 2024 and 2025, India’s IPO market has quietly done something important. It has priced risk. More than 15 green energy companies across solar manufacturing, bioenergy, and electric mobility have gone public. From Waaree Energies, Premier Energies, Ather Energy, Ola Electric, and TruAlt Bioenergy on the main board to Alpex Solar and Sahaj Solar on SME exchanges, these listings have created India’s first real valuation benchmarks. For years, climate tech valuations were built on global comparable and optimism. Now, for the first time, we have India-specific data showing what the market rewards and what it does not.

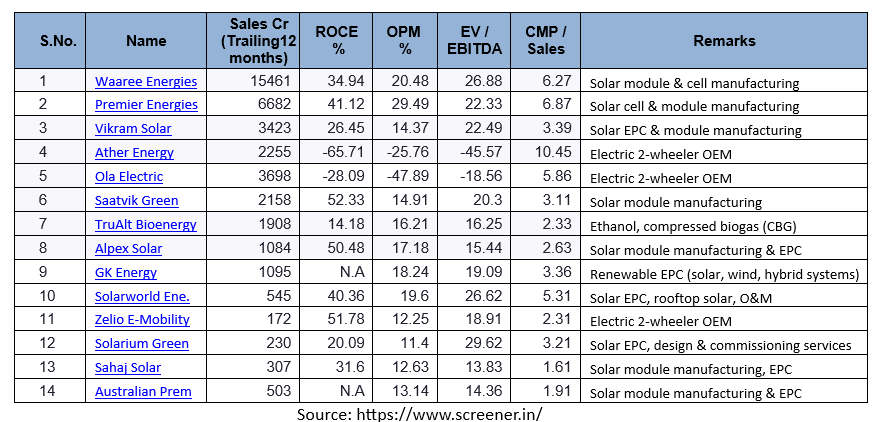

Valuation benchmarks for climate companies that got listed in last 2 years

1. The Market Rewards Integration and Strong Margins

The IPO tables tell a clear story.

Waaree Energies, a fully integrated solar player spanning modules, cells, EPC, and O&M, trades at 6x sales and 27x EBITDA. Premier Energies, similarly integrated, trades at 6.8x sales and 22x EBITDA.

Compare that with smaller EPC players like Solarworld Energy Solutions, Solarium Green, or TruAlt Bioenergy, which hover around 2–3x sales. Zelio E-Mobility, which largely assembles electric scooters, trades at 2.3x sales, while Ather commands over 10x.

Public investors are valuing integration, margin stability, and manufacturing depth rather than growth alone.

This has implications for early-stage pricing. If public solar companies trade at around 6× sales with 20–30% operating margins, a solar startup with sub ₹100 crore revenue and no profitability can deliver venture-scale returns, only if priced appropriately. Accounting for dilution across multiple funding rounds (from ~20% initial ownership to 12-13% at exit), and assuming the company scales to ₹1,000 crore revenue in 7 years with an exit at similar 6× multiples, entry valuations should be at or below 6× revenue to achieve at least 25% IRR. More conservative pricing at 3-4× revenue provides significantly stronger returns and margin of safety.

2. SME IPOs Are the New Series C

A less-discussed shift is the emergence of SME IPOs as credible exit paths.

Companies like Sahaj Solar and Solarium Green, each with around ₹300 crore in sales, have demonstrated that liquidity is possible much earlier, without waiting for a strategic sale or a global fund buyout. These companies raised ₹50–₹100 crore through public markets, achieving valuations that most venture-backed startups reach only by Series C.

This marks a structural shift for Indian climate investing. Venture funds can now design smaller, faster exit cycles, with the SME exchange effectively becoming the new Series C for solar EPC and bioenergy businesses.

3. EV Story Is Intact, but Performance Drives Multiples

Both Ather Energy and Ola Electric listed with revenue multiples of 6–8x, similar to those of profitable solar companies such as Waaree Energies, despite continuing losses.

EVs are seen as disruptors of a massive automotive market, while solar is more mature. EV companies build consumer brands with pricing power, whereas solar companies often operate as utilities or project developers with commodity-like economics.

However, performance has begun to differentiate valuations. Ola Electric has declined about 35 percent from its IPO, now trading near 5x price-to-sales, while Ather, which continues to gain market share, has nearly doubled from its IPO and trades around 10x sales.

4. A New Discipline in Climate Valuations

The Indian climate market is maturing faster than most expected. Public markets are signalling what “good” looks like, and it looks like 20 percent operating margins, over 30 percent return on capital employed, integration over scale, and profit over growth at all costs.

For investors, this also means the global green premium no longer applies blindly. A US-listed peer may trade at 15× revenue, but in India, 6x is the new ceiling unless the company has something truly proprietary.

The climate IPO wave is not just a liquidity event. It is a repricing event. It is forcing venture investors to mark to market, to base valuations not on potential but on precedent. That is not a bad thing. For the first time, Indian climate investing has real data, not just hope. Over time, this repricing will shape how early-stage founders build, prioritizing unit economics, governance, and public-market readiness over story-driven growth.